For those who couldn't be there, here is the text of the keynote address that I gave at the Entrust Languages Conference in Stafford yesterday. I also did my Be a crafty Languages teacher workshop, which you can find here.

We’re

on our way!

The

road is long

With many a winding turn

That leads us to who knows where

Who knows when

With many a winding turn

That leads us to who knows where

Who knows when

The Hollies released this single, He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother, a couple of weeks before I was

born. Its opening lines describe the

journey that we have taken so far along the road of Languages in Key Stage

2. It certainly has been long, with many

winding turns. It has taken us more than

10 years to arrive at where we are now, and our journey is far from over. The teaching of a modern or ancient language

has been statutory in Key Stage 2 for just about one academic year now. Can we already be sure where the road is

leading us, and when we will arrive at our destination?

The children’s

journey

Where do we want this road to lead? What is our destination? Is it a more linguistically adept

population? It is a less monolingual

country? Is it for languages to be

perceived as useful? Is it a solid

foundation of language learning and an enjoyment of the subject?

For most young people, the road will end abruptly at the

end of Year 9 (unless Nicky Morgan gets what she really wants and all students

really do have to continue with a language until they are 16) and their

destination will not, let’s face it, amount to much.

Our children in Key Stage 2, though, are at the beginning of the road. We are opening the door for them, gently guiding them through it and setting them off on their way with their backpack ready to be filled with useful things.

Our children in Key Stage 2, though, are at the beginning of the road. We are opening the door for them, gently guiding them through it and setting them off on their way with their backpack ready to be filled with useful things.

We hope that their journey will be long lasting. We hope that the road will lead them through

exotic colours and exciting experiences.

We hope that en route they

will pass, and maybe have the opportunity to explore, the many intriguing side

streets. And we hope that they will have

many songs to sing as they walk along, many stories to tell, and many friends

from all over the world with whom to share it.

We definitely hope that they do not wake up one morning to find that

they have to go back to the beginning and start their journey again…

What does the Key Stage 2 road look like? Well, it starts from nothing and ends in Year

6 with the “substantial progress in one language” that the Programme of Study

requires them to make. What are the

signposts on the way, the markers that will denote their progress? The statements in the Programme of Study are

vague, and can be difficult to decipher.

Dividing them up into skills helps, but it is only when we look at the

journey alongside the guidebook of the Key Stage 2 Framework for Languages that

it becomes clear.

For Listening, children are required by the new curriculum

to “understand spoken language from a variety of authentic sources”, to

“understand ideas, facts and feelings” and to “understand familiar and routine

language”. This is not to say that Year

3 children should be doing all of this. This

is the point that we should build up to by the end of Key Stage 2, as their

knowledge and confidence gradually increase.

Children are required to speak about people, places, things

and actions, to communicate ideas, facts and feelings, and above all to speak

in sentences. Children will speak using

single words in Year 3, phrases in Year 4, gradually building up to sentences

in Year 5 and Year 6. Children will

spend the 4 years of KS2 learning how to speak with increased confidence,

developing their strategies to help them to say what they want to say.

They will engage in conversations with each other, asking and answering questions and giving their opinions.

They will engage in conversations with each other, asking and answering questions and giving their opinions.

The children will have a magic key in their backpack which

will clarify and facilitate their journey.

They will learn the system of phonics in their language, the

sound-spelling link, the key to their journey being a success. This will lead to children who are confident

readers, who can take a word they have never seen before and pronounce it

correctly, thus sidestepping potential obstacles on their path.

Children will read lots of texts of different types, some

written especially for them as learners, others authentic texts from one of the

countries whose language they are learning.

Stories, songs, poems and rhymes will provide some of this content, and so

are the ever present white lines that run all the way along the KS2

highway.

Children will write at varying lengths during their KS2 journey,

beginning with single words in Year 3, working through phrases and sentences in

Year 4 and Year 5 and building up to paragraphs in Year 6. They’ll also be able to adapt sentences that

they read in order to create something new.

The children’s road will be built on a firm foundation of grammar,

which will hold the whole structure steady and in place. They will always compare the language they

are learning with English, to see how it is the same and how it is

different. This will enable them not

only to learn more about the new language, but also to reinforce their

knowledge of English. They will develop

skills as independent learners, such as dictionary skills, which will help them

to say what they want to say. Even if

the bridge between Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 3 has been knocked down, they can

confidently take an alternative route to the same destination with their

Language Learning Skills and Knowledge About Language in their backpack.

So the children have their journey, and their journey is

planned and its itinerary written by the route planners. Not Google Maps or the AA in this case, but

their schools and their teachers. In

turn, each school and each teacher has their own languages journey. They may well have started at a different

point and the route may have been different.

They may have been stuck at roadworks a few times waiting for the road

to be completed or for the way to be clear.

The teacher’s journey

As for my languages

journey, I'm just coming to the end of my twentieth year as a Languages

teacher. I spent fourteen of those years

in secondary schools, flogging away with French and Spanish at GCSE level. The last six of those years have been in

primary schools, altogether a very different experience. Younger children ask lots more questions. “Can I go to the toilet?” “When’s it

lunchtime?” and let’s not forget “Are you from France?”

My particular favourite question was “Madame, you know the Eiffel Tower, is it in Sunderland?”

My particular favourite question was “Madame, you know the Eiffel Tower, is it in Sunderland?”

One of the most common

questions, however, is "How do you know Spanish?" My answer is that I learned at school, the

same as them, and then went to university to learn some more and lived in Spain

for a while to learn even more. I tell

them that they have a head start on me as I didn't start learning Spanish till

I was 16. They are lucky to start

learning when they are 5. But then I

also say that I am still learning. I

learn new things about my languages and other languages every day. Languages adapt and morph on a daily basis,

and you never finish learning them.

So I am not only a

Languages teacher. I am also a language

learner. I would say that I am in my

38th year as a formal language learner.

I started to learn

French when I was seven, at middle school.

I grew up in Surrey, where there was at the time a three-tier

system. We changed schools at the end of

what are now Years 3 and 7. My learning

of French in the first year of middle school (equivalent to Year 4) comprised

writing out lists of things like numbers and months and colours, and sticking

them on the inside of our wooden desk lid so that we could see them each time

we lifted it up to get something out or put something away. We were given a French name and a

number. I was Denise and my number was

dix-neuf.

Then in the second year

(Y5 equivalent) we went to the new building and were allowed access to the

specialist French teacher, who we shared with the private girls’ school in the

next village. I can't remember exactly

what we did, but there was a lot of chalk and talk and grammar drills, and the

filling in of the little booklets, which I think were Eclair.

There was certainly no technology involved. In fact, there wasn’t any technology to be involved! We only learned one song - Savez-vous planter les choux? - and didn't play any games. There was no role play and certainly no pair or group activities. However when I left middle school in 1981, aged nearly 12, I knew avoir and être, the present tense of regular verbs, and had started the passé composé. I knew and could explain why boys said ma cravate and girls said mon chemisier.

There was certainly no technology involved. In fact, there wasn’t any technology to be involved! We only learned one song - Savez-vous planter les choux? - and didn't play any games. There was no role play and certainly no pair or group activities. However when I left middle school in 1981, aged nearly 12, I knew avoir and être, the present tense of regular verbs, and had started the passé composé. I knew and could explain why boys said ma cravate and girls said mon chemisier.

Then I went to

secondary school, which in this three tier system we started in Y8, and started

French again, from scratch. After half a

term we moved house, to the other side of Guildford. I arrived at my new school after the October

half term holiday. My year group was

coming to the end of a carousel of second language tasters. I did 2 lessons of Spanish and had missed the

German and Latin. The following week we

had to choose our second language. I

opted for Spanish as I'd tried it and because I have a Spanish godmother.

I was put in the Latin

group. Initially I was disappointed, but

in retrospect it’s the best thing that could have happened! Latin has been immensely helpful to my

knowledge about language, to my French, my Spanish and my English. It also helps to make me unbeatable at

certain quiz games.

Meanwhile I was

continuing with French and another new teacher with whom, again, the class was

starting again, but at least this time it was with Le français d'aujourd'hui and the Bertillon family. I remember telling my mum that I found French

boring. I fell out of love with

languages for a while.

I kept the same French

teacher all the way through secondary school, for all of the four years. Gradually it dawned on me that, far from

being boring, she was amazing, and had us (admittedly the top group) ready for

O level at the end of the 3rd Year (Year 9). We spent the next two years practising,

learning the past historic and writing countless 100 word essays (we did the

AEB board), enjoying the challenge of trying to cram in all the great

structures we'd learned. I have spent

many an idle moment trying to pin down exactly what her secret was.

So that's my language

learning journey from the late 70s to the mid 80s. The road was unembellished, modest and

traditional, but it suited me and I learned a huge amount.

I went to France for the first time – on a school day trip - when I was 14 and was quite happy to have a go with the speaking.

I went to France for the first time – on a school day trip - when I was 14 and was quite happy to have a go with the speaking.

However this road was

not easy for everyone. One of my friends

was in the same set as me for French, and she also was the recipient of an A

grade at O level. She also had done

Latin and so had a pretty good understanding of how language worked. She should have done A level French but the

thought of having to speak the language terrified her.

It was something we had hardly done in 4 years, apart from answering the odd question in class, and so the O level speaking exam with a visiting examiner was a bit of an eye opener.

It was something we had hardly done in 4 years, apart from answering the odd question in class, and so the O level speaking exam with a visiting examiner was a bit of an eye opener.

Your language learning

journey will have been different, and it may or may not have suited you. Many methods have come and gone, and in some

cases come again, since then.

The way languages are taught in primary schools now is worlds apart from the way I was taught in 1978. Our children’s current journey is very different to the one that we will have experienced ourselves.

The way languages are taught in primary schools now is worlds apart from the way I was taught in 1978. Our children’s current journey is very different to the one that we will have experienced ourselves.

My road started in the

south-east, and has led me gradually, and via a very circuitous route, to the

north-east. For a lot of the time I have

walked hand in hand with other people. I

don’t feel that it is a journey that I have had to make alone. Of course I have walked alongside my

teachers, lecturers and fellow students.

But I have also had the company along the way of good friends, my

Spanish flat mates, the family in France who housed me during my year

abroad. More recently I have walked

alongside and been supported by the many language professionals with whom I

have connected via social media over the last 10 years. I feel a little like Forrest Gump when he

begins his epic running across the USA and back and across and back. It starts off being just him but gradually he

is joined by more and more inspired runners until there are huge crowds running

with him. Except on my journey I am not

the leader, I am not at the front of the group.

The crowds are mutually supportive, taking it in turns to direct and

lead.

How has your language

learning journey been? Have you

travelled alone, or have you had others walking with you? Are you lonely and looking for someone to

share your journey?

It is true that the day-to-day life of a teacher is not an

easy one. Particularly if you’re a

teacher who has had to add another subject to their already busy planning and

teaching schedule. It’s easy to get

stuck in a rut where there are no fresh ideas, where you can’t think round a

problem to find a new way of doing it that is just right for your class, where

you can’t find the information that you need to deliver the lesson to your own

high standard. And how many times have

you spent ages on a resource only to find later that you have in fact reinvented

the wheel?

As they said in High School Musical, we’re all in this

together. Whether we like it or not,

whether we are prepared to admit it or not, we all face the same challenges and

the same pulls on our time. We’re

working towards a common goal but we all have different tools at our

disposal. We have to support and help

each other.

The year before I became an AST I did a “Becoming a subject

leader” course. It taught me that I

didn’t want to be a subject leader, but it did teach me some useful things too.

Like how important it is to build a culture of sharing, supporting and

networking amongst your colleagues.

If you want to connect with a wider audience, there are

different forums and other online “outlets” that you can access. For example there is the TES Forum, where you

can discuss languages and their teaching, although the Modern Languages forum

isn’t half as busy as it used to be. I

can’t recommend Twitter and the #MFLTwitterati highly enough for keeping you up

to date with cutting-edge ideas and for the camaraderie. If you follow my Primary Languages UK Twitter

list, you can keep in touch with and get information from over a hundred

primary languages teachers, specialist and non-specialist, as well as from

organisations, publishers and suppliers.

If you are a Facebooker, there is the Languages in Primary Schools

group, a closed group which has over 1700 members, and which is both immensely

supportive and always positive.

It is a well-known fact that many of the teachers who find

themselves having to teach Key Stage 2 Languages are in need of some help with

the language itself. They may be lacking

in confidence in their own ability, or needing help refreshing the language

that they learned a long time ago at school.

There has not been much money forthcoming for the majority of primary

teachers who require upskilling, so the arrival of the Association for Language

Learning’s network of Primary Hubs has been a godsend. They exist all over the country so find one

near you. They are free of charge and

allow you to link up and meet with other professionals who are in the same boat

as you.

The children have their

language learning journey, and we as teachers have our own. Everyone is at slightly different points

along their own individual road. And everyone has their own way of walking.

The teacher’s way

What is our “way” in

terms of what we do in the classroom?

One of our main aims is

to get the children involved in their learning.

They are no longer the passive recipients who sit silently in rows and

then complete pages of exercises in their books. We know that children learn best when they

have the opportunity to help, support and explain to each other. They learn best when they take part in an

activity that they perceive to be fun, interesting or different. They learn best when they have the

opportunity to do the things that young children like to do: singing, dancing

around, playing and laughing.

Confucius said:

“I hear and I forget.

I see and I remember.

I do and I understand.”

which is further clarified in the words of this Native American proverb:

“Tell me and I’ll forget.

Show me and I may not remember.

Involve me and I’ll understand.”

Both sayings emphasise the importance of children’s participation and involvement in their learning.

“I hear and I forget.

I see and I remember.

I do and I understand.”

which is further clarified in the words of this Native American proverb:

“Tell me and I’ll forget.

Show me and I may not remember.

Involve me and I’ll understand.”

Both sayings emphasise the importance of children’s participation and involvement in their learning.

When I was a secondary teacher, my colleagues and I had

preconceptions about primary classrooms.

We thought that children were always up and down and out of their seats

and unable to sit and listen. It’s how

we used to account for Year 7’s fidgeting and neediness. But now I know differently. Primary children work collaboratively, in pairs

and in groups. They change activities

frequently to keep the pace going and to maintain interest. Seating patterns are important and there is

also a strong culture of helping others.

Much primary learning is characterised by active learning. Children read, talk, write, describe, touch, interact,

listen and reflect. They learn by doing,

thinking and exploring through planned and quality interactions. The child is not a passive observer.

So what sort of activities and materials should we be

aiming to include in our language lessons?

The learning set-up is a bit different to other subjects as the children

rely more on the teacher as the source of knowledge than maybe they do

elsewhere.

Let’s start with flashcards. Of course they are very useful for the

teacher when presenting new language to the class, but once the teacher has

finished with them, they can be handed over to the children to help them to

practise the new words and phrases. They

are easy to manipulate and require no ICT after you’ve made them. And they always work when the computer, for

some reason, doesn’t. Children are very

good at thinking of ways to practise new language in pairs or groups with sets

of small cards.

Dominoes are a pair or group activity ideal for revising

prior learning or indeed for practising new language. There is the possibility of matching up

words with pictures, words with words or even words with numbers. How about matching up the two halves of a

sentence? There are many possibilities,

all of which require the children to discuss the answer together and arrive at

a decision.

Moving on one step from dominoes are shape puzzles, or

Tarsias, as they are now more commonly known.

Each side of each shape has a word or picture that needs to be matched

with another word or picture so as to create the final shape. When the Tarsia is finished, it can be used

as a reference tool, stuck down on sugar paper and added to.

Sorting activities like Trash or Treasure or Venn diagrams

oblige children to work together to find the links between words and phrases. The more sorting they do, the more familiar

they become with the selection of words and their functions.

For practising structure in writing try a game of

Showdown. Each group of children has a

set of cards with phrases or sentences in English or in picture form that need

to be written in the target language. The

group captain chooses a card and puts it on the table for the rest of the

children to see. They each write on

their own mini whiteboard the phrase or sentence that the card requires. When they have all finished, the captain says

“Showdown” and all members of the group show what they have written. They discuss, looking at the evidence they

now have, what the correct answer is.

For another way to practise structure, use dice,

multi-link, Lego or paper chains.

Each number or colour relates to a part of a sentence or an individual word.

Each number or colour relates to a part of a sentence or an individual word.

There is even something as simple as giving each child a

Post-It and asking them to test each other on the words you have been learning

and note down the results on the Post-it for you. Everyone will be busy, it will only be a

short activity, and there won’t be lots of children sitting bored and restless

while the teacher has to go round testing individuals.

When the class is playing a game like Chef d’Orchestre or

Hide and Seek they will be enthusiastically speaking the language, but not

thinking about it – the language is the means of winning the game or helping a

classmate to find the answer.

And going right back to basics, every time the children

repeat a word and perform an action to go with it, they are responding

physically to the language, but also being active learners and involving

themselves in the learning.

The children have their

journey, each school and teacher has theirs, and we all have our own way of

walking, our own style and our own preferences.

The national journey

Where are we in terms

of our national journey?

I recently invited

teachers to complete a survey so as to find out a bit more about what is

happening in the world of Key Stage 2 Languages. There were 160 responses, representing 160 schools,

which admittedly is only a tiny proportion of all the schools in England, but I

think the answers give a good idea of what is happening.

76% of schools offer

French, and 34% Spanish. You’ll see that

the percentages don’t add up to 100, and of course this means that some schools

are offering more than one language.

Some schools offer two, and a smaller number offer three. As you can see, the percentages for German,

Italian and Mandarin are very low compared to French and Spanish. This is probably largely to do with teacher

expertise and experience, as well as being a reflection of the number of

resources and the amount of support that is available for each language. It is interesting to compare this with the

same question posed to KS3 teachers.

There is a lot more German offered in KS3 while the French and Spanish

are quite similar.

Language learning in

the primary phase is only statutory in KS2, but about half of respondents said

that their children learn a language in KS1 as well. In the case of the school where I teach

French, French lessons happen every other half term, so a half term on, half

term off pattern. Starting in Year 2

means that by the end of KS2 they have had more time overall.

More than half of the

teaching is done by language specialists.

It is difficult to know how much the results of this survey are skewed

by the profile of those responding.

Although more and more schools do seem to be going down the route of

having a specialist do their Languages lessons for them. I have been approached by 3 schools in the

last few weeks. We need to bear in mind

the impact that this will have on staff skills.

If teachers are at a school where a specialist delivers the language

lessons, and they then move to a school where they are expected to deliver the

language themselves, they will have no experience to draw on.

The vast majority of

children have their language lessons once a week, throughout Key Stage 2. The new Programme of Study doesn’t specify a

time allocation for the teaching of Key Stage 2 Languages, and the DfE has been

less than forthcoming. The Framework

recommends an hour a week, saying that this hour can be cut into, say two half

hours or three lots of 20 minutes. There

are some schemes of work, the Jolie Ronde for example, whose plans allow for

several short lessons per week rather than one long one. It is surprising, therefore, that very few

schools appear to be going for the “little and often” model. Maybe it’s just that it’s easier to timetable

for and actually teach a longer session.

The majority of

children have languages lessons that are between 30 and 60 minutes. Personally my Spanish lessons work out at

about an hour, and the French at about 45 minutes. It’s also good to see that Year 6 don’t

appear to be missing out on their language lessons too much.

It’s when examining

some of the issues raised by this survey that we trip over some of the

obstacles that have been left scattered on our road. One the biggest obstacles is the big thorny

briar that is Key Stage 2-Key Stage 3 Transition. The word Transition in itself is misleading,

as it implies a change. However we now

have a 7-14 Languages continuum, and we should be aiming for the journey to be

as seamless as possible to maximise the progress. It is clear, though, that at the moment this

is not happening.

I asked teachers if

they sent transition information for their Year 6s to the secondary

schools. 26% of teachers said yes, 56%

said no. I also asked KS3 teachers if

they receive information from their feeder primary schools. 8% said that yes, they receive the

information from all or most of their feeders.

34% receive information from some of their feeders. 48% of secondary schools do not receive

anything. This means that about half of

secondary teachers do not know what their new Y7s will have been doing in KS2,

the language that they have been learning, and what they have covered. If we don’t tell them this information, we

are doing the children a huge disservice and probably consigning them to a Year

7 of repeating what they have already done in Key Stage 2.

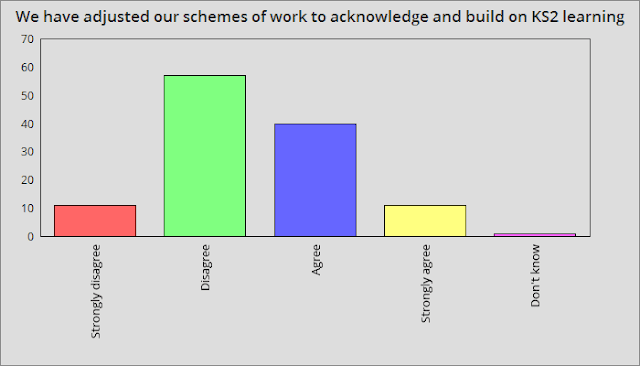

In order to look in

more depth at the situation I asked some more questions of the Year 7 teachers. Only 21% agreed that their new Y7s will

continue the same language that they started in KS2. Only 40% agreed that they have adjusted their

Year 7 Schemes of Work to take into account KS2 experience. 63% agreed that they disregard KS2 experience

and effectively start again with Year 7.

All of this is disheartening

for those of us who spend so much time investing in the linguistic future of

Key Stage 2 children. It is clear that

the two phases have a lot to do.

Communication must take place and those links must be made. Transition is so important, and can’t be

ignored under the pretext of “We have so many feeder primary schools it would

be impossible” or similar. We have to

make KS2 Languages work. We have come too

far down the road to let it fail now.

Transition isn’t our

only obstacle, of course. There are

other obstacles such as Ofsted, who are reluctant to tell us what exactly they

will be looking for apart from that it will be inspected in the same way as the

other Foundation subjects. They don’t

appear to be taking a huge amount of interest in the subject, and don’t appear

to be voluntarily observing lessons during inspections.

Conclusion

I’m on my way I’m making it

I’ve got to make it show, yeah

So much larger than life

I’m gonna watch it growing

I’ve got to make it show, yeah

So much larger than life

I’m gonna watch it growing

It has been a long,

long road, but we have the destination in our sights. We’re on our way, we’re making it. Great things are happening, we’ve got to

make it show, and we are making it show.

We need to continue along the same road, wearing the same very suitable

shoes, with the same backpack full of our best tips and tricks, walking briskly,

resolutely and confidently, watching the children’s learning and love of

languages growing.

We’re on our way!